Life Advice

A few weeks ago, I had lunch with my Godson, a sophomore in college. Towards the end, he asked, “Do you have any career advice for me?”

I immediately thought of this blog post on Capital Gains that talks about the dangers of giving life advice based on your own experiences. From the piece:

"…agreeable extroverts will probably tell you that the best thing you can do for your career is to meet as many people as possible, so you have lots of second-degree connections through which you can hear about opportunities. This is probably true for them, but someone who naturally loves nerding out about esoteric programming languages would dismiss this advice out of hand—meeting people is hard, getting them to like you is harder, so you should focus on simple, achievable goals like getting a thousand stars on your Github repository.”

Success comes from a combination of hard work, luck, and skill at the work one is doing. However, a less often discussed component is our inherent temperamental traits. In other words, depending on who you are, some stuff is easy for you, and other stuff is really, really hard. And this matters a lot.

Personally, it’s very easy for me to wake up in the morning and go to the gym. I almost don’t even think about it. I just go. On the other hand, it’s very difficult for me to keep in touch with friends and acquaintances. It takes lots of work.

I have a friend who is the exact opposite. He has struggled his whole life to find a way to build a consistent workout routine. I’ve seen him try enough to know that I don’t have more motivation or willpower than he does. I’m certain of it. It’s just inherently easier for me to do the thing we’re both trying to do. Conversely, he effortlessly keeps in touch with a huge network. Regular phone calls to friends when he’s driving. He stops in on people when he’s in town. Remembers birthdays. Sends gifts. I have to really work at it. It’s hard for me. Of course, it’s important to him, and he does it with purpose, but I can see that it’s also easier for him than it is for me.

Obviously, this applies to our work as well. So if you advise someone to get into the legal profession and, despite your personal success in that field, they have a really hard time consuming large amounts of complex text for long periods of time, all else equal, that person is really going to struggle, and you’ve given them really bad advice. Similarly, if you tell a math genius who is shy to get into a sales job early because that’s where the money is, you’re really setting that person back. Both because they’ll really struggle at the job and because they’ll suffer from a very high opportunity cost of not building multimillion-dollar machine learning models for an AI company or something like that.

People giving career advice are often biased and tend to lean towards their unique, long, and winding path to success. That’s a bad idea. The most extreme example is “follow your passion.” This is great advice if your passion is financial analysis, but not so good if it’s skateboarding.

All of this is to say that giving career advice is really hard, and we have to be cautious about not sending younger people down our paths because what worked for us in so many ways may never work for them.

A while back, I wrote a summary of my best career advice at the time titled 15 Things I Wish I Knew Before I Started. I went back to take a look at it to see if I was guilty of giving biased career advice. It's not perfect, but I was happy to see that it holds up fairly well.

Anyway, if you’re wondering what I told my Godson, I came up with two pieces of (hopefully) unbiased advice:

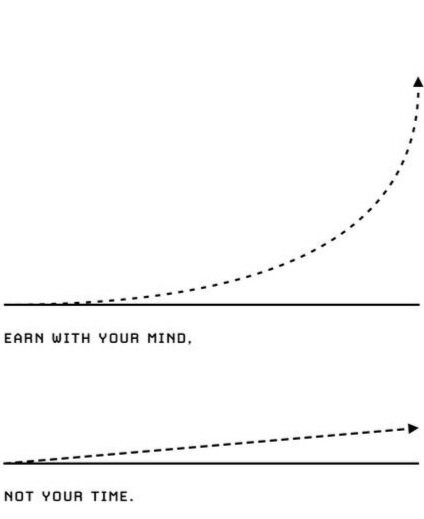

1/ Pursue opportunities with leverage (adapted from Naval Ravikant). You may not be able to do this in your first job out of college — honestly, your first few years are probably going to suck, so you’ll have to keep your head down and grind for a while — but always try to ultimately pursue work where your outputs are disproportionate to your inputs.

2/ Leave something on the table. Leave jobs, partnerships, and business relationships where the other person feels like they got more from you than what they paid. That results in a reputation with a surplus where people will feel good about working with you and will say good things. That surplus compounds. If someone thinks you’re good and they hear from someone else that you’re good, now they think you’re really good, and they’ll tell people that you’re really good, now those people think you’re really good. And on and on. If you do this well, your career will feel less like you’re climbing a ladder and more like you’re sailing on a boat with a steady wind at your back.