Enterprise Network Effects & User Retention

A16z had a good podcast the other day talking about startups with network effects and it got me thinking about network effects in enterprise businesses. A product has network effects when the product becomes more valuable as more people use it. Your fax machine was more valuable when more people bought fax machines — you could fax more people. Facebook is more valuable when more of your friends use it -- you can view more photos of your friends.

A16z had a good podcast the other day talking about startups with network effects and it got me thinking about network effects in enterprise businesses. A product has network effects when the product becomes more valuable as more people use it. Your fax machine was more valuable when more people bought fax machines — you could fax more people. Facebook is more valuable when more of your friends use it -- you can view more photos of your friends.

Businesses with network effects scale exponentially. The reason is that their users effectively become extensions of their sales and marketing team. A Facebook user has an inherent incentive to get other people to use the product. This is a beautiful way to grow and scale a business.

In order to maintain growth, though, these businesses need to ensure that they're retaining the users they acquire -- which is an entirely different challenge. This is relatively easy in B2C because, in theory, the user can be part of the network forever. This is much harder in B2B because users — employees — turnover at the rate of ~20% per year (people get terminated and quit). So in theory, the entire network turns over every five years. And while it's true that often an employee that leaves is replaced by another this kind of churn is not a great way to scale.

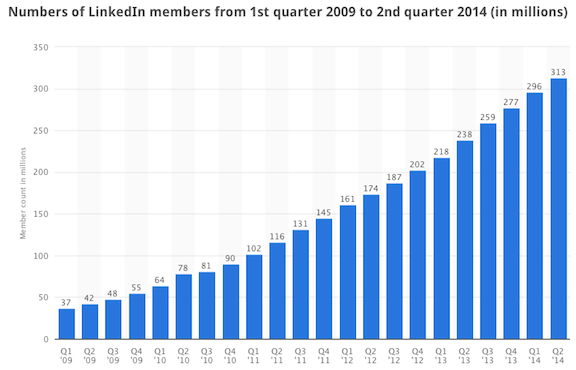

That said, some B2B network effect businesses have found ways to retain some users after they change jobs. LinkedIn, Evernote, Wunderlist, Dropbox are a few that come to mind. Not only do these businesses retain their users as they move from job to job, these users also drive new customer acquisition by promoting the product within their new companies (what I refer to as B2E2B). These businesses are seeing network effects drive new users, retention of those users when they move to a new job, and new sales driven by those employees that evangelize the product in their new companies. This how an enterprise business can grow like WhatsApp.

But this isn't easy. Enterprises are concerned about their employees using the same software as they move from company to company -- e.g. they don't want an employee taking their Evernote notes on to their next company. And the product customizations and switching costs may be so high in some cases that the value of the product doesn't translate from one company to another.

The challenges are significant; but the businesses that build an enterprise product with 1.) inherent network effects to drive new users and 2.) the ability for those users to stay engaged with the product as they move from job to job will be the networks that win.

Because of the emergence of crowdfunding, angel syndicates, private exchanges, and a lower regulatory bar to invest in early-stage startups, it’s likely that we’ll start to see much more consistency between private valuations and subsequent public valuations. Also, don’t underestimate tools like eShares that help founders manage complex cap tables. I can vividly remember being at a startup where we didn’t want to give out stock options to consultants for no other reason than it would’ve added too much complexity to our cap table. It's a lot easier for a private company to manage thousands of investors than it used to be.

Because of the emergence of crowdfunding, angel syndicates, private exchanges, and a lower regulatory bar to invest in early-stage startups, it’s likely that we’ll start to see much more consistency between private valuations and subsequent public valuations. Also, don’t underestimate tools like eShares that help founders manage complex cap tables. I can vividly remember being at a startup where we didn’t want to give out stock options to consultants for no other reason than it would’ve added too much complexity to our cap table. It's a lot easier for a private company to manage thousands of investors than it used to be.