"User-First" Client Acquisition

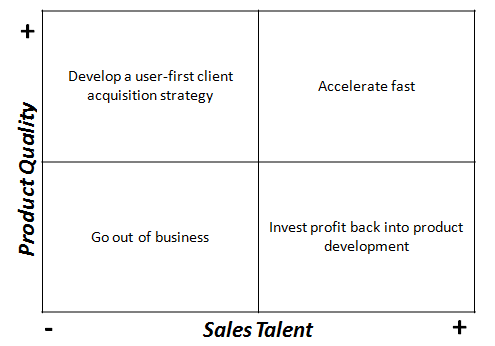

I built the simple framework below to help me think through the enterprise product conversation happening yesterday.

A B2B company could find itself in one of four situations. The goal is to be in the top right quadrant (good sales talent, good product quality) so that you can simply accelerate what you’re doing. But the most interesting to me – and the one that I think will be the fastest growing – is the top left quadrant: when you have a good enterprise product but little or no sales talent. I’ve seen more and more startups come along that have super cool products but no enterprise sales experience or talent.

The old fashioned solution to this problem would be to hire, partner or find an experienced distributor that could move product for you. But largely because of what I think is an increasing hesitancy among early stage companies to over-invest in sales & marketing, there’s a ‘user first’ strategy that seems to be gaining traction. Companies like Yammer are providing value at no cost to individual users but charging the company for “premium upgrades”: system integration, security, admin rights, etc.

At its core, “User-First” seems like a no-brainer: get employees to use your product and love it so much that they demand their companies purchase the upgrade. But like most things, the challenge may lie in the details of the sales process; i.e. how does this approach align with a potential client’s buying process? Good B2B salespeople have adapted their process to match their prospects’ buying cycles. And in my experience the buyers like the process, control, security (and bureaucracy) that these cycles allow.

Products that decide to go “User-First” will have to learn these details and adapt their upsell process to fit in neatly with institutionalized buying cycles. If they can’t do that well, “User-First” will simply be a fancy lead generator and sales talent will continue to be a requirement for B2B success.